the boy with his hands raised

As I mentioned here on April 10, when I was in my early 20s, I tried to imagine the life of the boy with his hands raised being led from the Warsaw Ghetto. I spent months with him, I kept his image before me daily. I looked into his eyes, and I tried to look through his eyes.

the boy with his hands raised being led out of the Warsaw Ghetto

I have known this photograph nearly all my life. It is a photograph known to many others as well. I mentioned in my earlier post that it was possible that the boy may not have died in the Sho’a.

Since then, I have studied the photograph more and some of the controversies surrounding it. Of particular help was the book by Richard Raskin: A Child at Gunpoint. A Case Study in the Life of a Photo. Aarhus University Press, 2004. ISBN 87−7934−099−7. While it is possible the boy may not have died in the Sho’a, Raskin’s book pretty thoroughly proves that those who either claim to be the boy, or claim that he did survive have little evidence to confirm their stories.

The photo is so powerful that people seem to want to be that boy. Others have written poems (rather poor, in my estimation) to him.

let’s get real

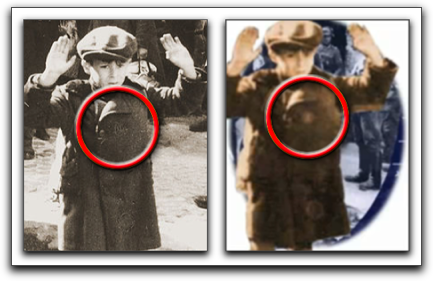

Why does Fischl call him “Polish”… because he (Fischl) is Hungarian by birth? Why not call him “Jewish”? If he was simply a “little Polish boy” there would be no photograph. Take a good look at the original photo above. Is there a star on the boy’s coat? How many machine guns are pointed at him? (Of course, one is more than enough, but if Peter Fischl wants to write a poem about it he should perceive its details accurately first.) Along with the photo, this poem has taken on a life of its own; so much so that in order to make the photo match the poem, a “star” was “photoshopped” onto the boy’s coat. I’ve brought the two images together here (the star on the boy’s coat appears at minute 1:57 — 2:09 in the video):

compare photos of boy with “star” (circled)

There is no question that the photograph is powerful. It is powerful enough without being edited. Raskin examines the photograph from a visual perspective. Unlike many photos from the Sho’a this one does not make us avert our eyes because it is too harrowing. Nonetheless, the scene it depicts is outrageous: a young, unarmed, boy (among many others) is forced to surrender. A high number of polar opposites are depicted (in Raskin’s words):

- SS vs. Jews

- perpetrators vs. victims

- military vs. civilians

- power vs. helplessness

- threatening hands on weapons vs. empty hands raised in surrender

- steel helmets vs. bare-headedness or soft caps

- smugness vs. fear

- security vs. doom

- men vs. women and children

Regarding the boy himself, he stands alone in his own space. Additionally, the boy’s face appears near the “Golden Section” or “Golden Ratio” of the photograph. It is an outstandingly gripping photograph.

the boy with hands raised and the Golden Ratio

The photo is one of many, taken as the Nazis destroyed the Warsaw Ghetto during the Uprising. It was part of illustrative material for what became known as “The Stroop Report”, named for Jürgen Stroop, the commander of the German forces responsible for liquidating the Ghetto. (Stroop is the man in the hat, not helmet, who is not obscured in the photo below.) While we do not know for certain who the photographers for the report were, two names are closely associated with it: Albert Cusian and Franz Konrad. Either one of them might have been the one to take the photo of the little boy. The identity of only one person in the photo of the little boy is known for certain: the soldier standing in the sunlight on the right side of the photo: Josef Blösche. Blösche appears in at least one other photograph from the liquidation of the Ghetto (in the photo below, once again, standing on the far right).

Jürgen Stroop directs the burning of the Ghetto (in center, in hat, not helmet, not obscured) while Josef Blösche (on the far right) watches

other photos of the liquidation

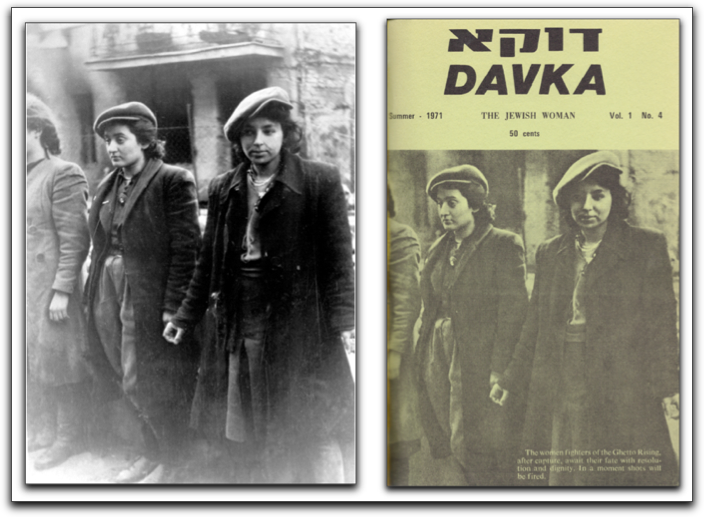

A few other photographs of the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto have been used elsewhere. One with which I have had direct personal involvement is captioned in the Stroop Report “Hehalutz women captured with weapons”. Interestingly enough, we do not see any weapons in the photograph.

Hehalutz women captured with weapons; used on the cover of Davka, Vol. 1, No. 4, Summer 1971

The photograph was used on the cover of Volume 1, No. 4 of Davka (Summer 1971) devoted to “The Jewish Woman”, the original locus of Rachel Adler’s article “The Jew Who Wasn’t There”. These women were definitely there. The caption in the lower right corner of the cover reads (inventively) “The women fighters of the Ghetto Rising, after capture, await their fate with resolution and dignity. In a moment shots will be fired.” The cover was also made into a poster that was distributed around Los Angeles. Copies of it still hang in some homes.

but I digress… Jürgen Stroops words

While reading about the liquidation I came upon this tidbit:

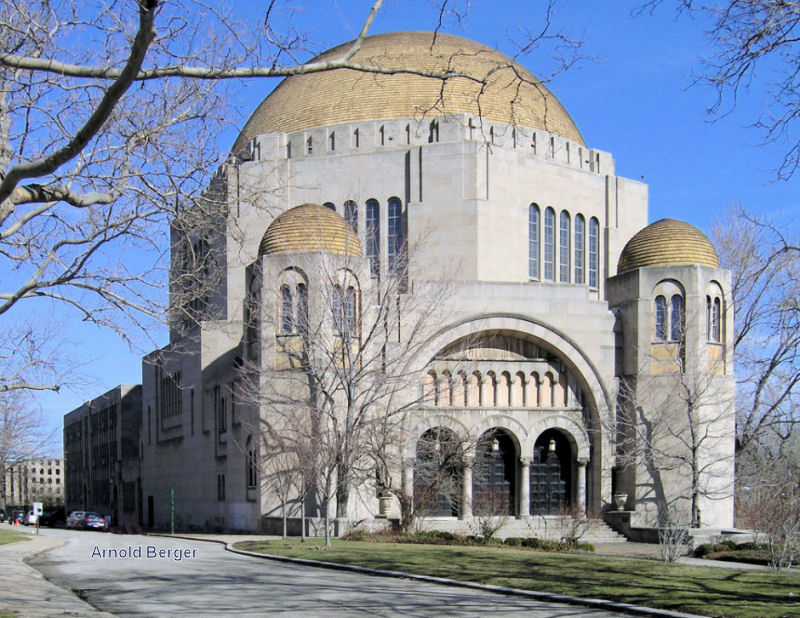

After a careful review of the situation, I decided to end the Grand Operation on the evening of May sixteenth, 1943, at eight-fifteen in a suitably artistic manner — by blowing up the Great Synagogue near Tlomacka Street. Krüger had suggested this finale during his Warsaw visit, giving Jesuiter plans prepared by his top engineers in Krakow, showing how and where to bore holes and place explosives. This operation took ten days to prepare.

the great synagogue of Warsaw at Tłomackie street

[Jürgen Stroop in Kazimierz Moczarski, Conversations with an Executioner. Edited by Mariana Fizpatrick (Englewood Clifs: Prentice-Hall, 1981; orgi. published in Polish 1977), page 164.]

There are 53 photographs in the Stroop Report. We don’t know whether the sequence in which they appear in the Report is chronological or was set for “artistic” purposes. For similar artistic purposes, I imagine that the photograph of the little boy was taken that very last day… May sixteenth, 1943.

May sixteenth, 1943

this is posted on May sixteenth, 2010

My parents were born and grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. Their parents were immigrants from Ukraine (actually, paternal: Chernigov [Chernihiv] Pale of Settlement and maternal, some 450KM north, from “Snofsk” on the Dnieper), not far from Vitebsk. At the time they left for the U.S. more than one third of the local population of Chernihiv and half of Vitebsk was Jewish.

In Cleveland, their families lived near Euclid Ave. and “the Kinsman Streetcar”. My grandparents were either atheists or (perhaps the maternal ones) agnostics. Both sets of grandparents were involved in Jewish life. Hillel Hurvitz was active in the Yiddish Workers’ Chorus. They certainly would not have joined the Reform congregation.

The Temple, Cleveland, Ohio

Nonetheless, we have always known that my parents were married in “the rabbi’s study at the Temple” during sefirat haOmer. A “special dispensation” was made because my father was in the army stationed at Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Texas. Neither of my siblings are aware of any photos from the wedding itself. In fact, I don’t even remember seeing their ketubah.

Nathan Hurvitz & Faye Hurvitz as newlyweds

So, on May 16, 1943, at approximately the same time that Jürgen Stroop declared the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto as having been complete with the destruction of the Reform Great Synagogue near Tlomacka Street, at a Reform temple approximately 4500 miles or 7000 kilometers away in the west, though I was not yet a glimmer in my parents’ eyes (my sister was born 10 months later, 3 years before me) my life was beginning.

Today, very little is as it was then. The area of the Warsaw Ghetto was completely razed by the Nazis.

from the Wikipedia: Ruins of Warsaw Ghetto, smashed into the ground by German forces, according to Adolf Hitler‘s order, after suppressing of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943. North-west view, left — the Krasiński‘s Garden and Swiętojerska street, photo taken in 1945

Almost nothing of the wartime rubble remains. Debbie and I had the opportunity to visit Warsaw during Pesach of 2006. We made a point of finding a bit of The Wall.

a remainder of the wall enclosing the Warsaw Ghetto

The residents of Warsaw have built a new city and the area of the Great Synagogue near Tlomacka Street is now known as Bank Square (the Blue Tower) Błękitny Wieżowiec.

yet, the boy lives on

As I mentioned in my April 10th posting, I have used the image of the boy with his arms raised for my own purposes.

leaflet detail

I am hardly alone in this. Aside from the “poem” by Peter Fischl, Raskin reviews a number of instances in which the image of the boy with raised hands appears in artistic and political works. Though I have been unable to find the film on YouTube, Raksin gives a very detailed (with stills) reconstruction of the movie With Raised Hands (Polish title: Z podniesionymi rekami) by Mitko Panov. The film won the Golden Palm Award for Best Short Film at the Cannes Film Festival in 1991. In Raskin’s words:

The film is pure fiction in the sense that the writer/director imagined what might have happened when the photograph was taken.

From the stills and shot-by-shot reconstruction available in Raskin’s book, it is both very inventive and moving.

Other creative works include the British television show The Glittering Prizes (the final episode) and the works of Samuel Bak. I can imagine that many Christians would feel that these two images by Bak are an affront to their religious sensibilities. And, on many levels I agree. Neither the boy, nor any of the millions of Jews and others murdered by the Nazis died for anyone’s sins.

Samuel Bak paints the boy with hands raised

I understand and appreciate how Christians might feel when a sacred image is used by others to express something that they might not identify with. And so I categorically reject this attempt at “equivalence” when Israeli artist Alan Schechner uses the image and connects it with a young boy captured during the Intifada in a video that has one boy, recursively, holding the photograph of the other.

Alan Schechner’s transformations

a confusion of categories

I am not alone in opposing Alan Schechner’s use of the image. But, I also disapprove of this use of the image because of what I sense is a creeping identification of other events as “equivalent” to the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. This week, as I write this post, a button is available for auction on eBay which identifies the massacre of Sabra and Shatila in 1982 with the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto.

lapel button comparing Warsaw Ghetto in 1942 with Beirut in 1982

These two events are of different categories, and cannot be compared. At the same time, while we need to beware of our strength and be ever vigilant of abuses, we also need to guard against such comparisons. And so…

The following button also uses the image of the boy with his hands raised. I have never worn it, nor would I. It was produced, probably, sometime in the early 1970s by the Jewish Defense League in New York.

the boy with his hands raised (lapel button)

| Date: | 1970s |

| Size: | 5.1 |

| Pin Form: | straight |

| Print Method: | celluloid |

| Text | DO NOT FORGIVE DO NOT FORGET |

your lapel buttons

Many people have lapel buttons. They may be attached to a favorite hat or jacket you no longer wear, or poked into a cork-board on your wall. If you have any laying around that you do not feel emotionally attached to, please let me know. I preserve these for the Jewish people. At some point they will all go to an appropriate museum. You can see all the buttons shared to date.

Some of the photos, especially that of the two young women who had been arrested (OF COURSE their weapons would have been taken away from them by this point) were used on the cover sleeve of an LP of Yiddish songs by a German group ‘Zupfgeigenhansel’in the 1970’s.

Walter,

Thank you for that update. I’m glad to learn of Zupfgeigenhansel and more about them from the German version of Wikipedia and through them, about the works of Theodor Kramer.

Here’s the group in Cologne singing a song by Mordechai Gebirtig, and that same song (“Hulyet, Hulyet Kinderlech) sung by some students at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. Gebirtig is probably best known for his song S’brent, covered here by Oy Va Voy, which is, I think, a British group.

Hi, Mark.

Interesting story about that famous picture.

In 1975 I spent a few weeks in DDR, much of it staying with an elderly couple who had been friends of my parents in Berlin, before they fled in March ’39, minutes ahead of the Gestapo. The couple had been Communists since before the Nazis came to power in ’33, and had risked their lives to keep my maternal grandmother alive by bringing her small packages of food every few days, until she was taken to Auschwitz in ’42.

Staying with this Communist couple in E. Berlin (Koepenick) was a real eye-opener for me.

One story they told me was about the soldier holding the rifle just to the right of the boy: in ’53 he was located teaching in the DDR, and was brought to trial and hung. Coincidentally, another friend of mine, composer Earl Kim, who taught music at Harvard (known for writing a violin concerto for Y. Pearlman), wrote a piece inspired by that picture. He said the boy’s eyes haunted him for years…

chazak

stan

Hi Stan,

Good to hear from you.

Yes, the man to the right is Josef Blösche. You can read more about him at the Wikipedia article.

I had never heard of Earl Kim, nor his violin concerto. It is not mentioned by Raskin in his book. I would like to hear it some day.