preparing for my beloved

As we begin Elul, the month before Rosh haShannah, preparations for the new year start.

blowing shofar

As I wrote last year (August 20, 2009) at this time, the Hebrew word אלול is considered an acronym for the phrase from the Song of Songs: 6:3a…

אני לדודי ודודי לי = I am my beloved’s, and my beloved is mine.

The phrase is meant to suggest a loving relationship between the Creator and the Jewish people, or at this time of year a much more personal relationship between God and each individual who is ready to re-evaluate hirs actions as the world begins to constrict (at least in the northern hemisphere). [“hirs” is my own contraction or combination of “his” and “hers”]

To help in this preparation, I have brought forward links to a number of tools I developed last year at this time. During the month of elul and through Yom Kippur, they will available in the sidebar on the right.

name the day

One way of preparing is to blow shofar each day of Elul to “wake us up” to the tasks ahead.

There are many ways of approaching Rosh haShannah. Two of the terms that refer to this day can help us focus on its immediate meaning for us as individuals. These are Yom Harat Olam: The day of the creation of the world and Yom Teru’ah the day of the shofar blast; the latter complements and adds meaning to the former.

Long ago, there was debate as to which season should be chosen as that for the celebration of the New Year. One reason that this time, the new moon closest to the autumnal equinox was selected was the unique coincidence that the first word of the Torah בראשית is an anagram (has the same letters, but mixed up in a different sequence) as the Hebrew term for today’s date: א בתשרי (the first day of the month of Tishre). The beginning began on this day, Rosh haShannah! Not only that, the ancient rabbis taught that it was on this day, Rosh haShannah, and in the first hour of this day that the thought came to the creator to form Adam: humanity.

This concept of a created world is of great importance. It is so significant that we Jews celebrate the event of the creation. We do this by recognizing that just as the world was created and is created anew each year, so we, as creatures within the world have the ability to renew and be renewed each year. In fact, think of it a moment: of all the things in this world with which we come into contact, what is the most complex single creation over which we have the ability to shape, renew and improve? Ourselves. The idea of a created world and re-created human being serves as a basis for the concept of free will. In fact it is so important that the ancient rabbis believed that when an individual, —let’s say I— act incorrectly during the year, a record of the transgression is inscribed in faint ink in the Book of Life (like writing in lemon juice on paper). If I repent and correct my ways during the ten days of repentance, the record is erased. But, if I don’t, it is rewritten in indelible ink (the heat generated by my not repenting causes the lemon juice to become visible), and these acts become an in-expunge-able part of my character.

invisilbe ink message revealed

unabashed confrontation

And so, at this time of year, we are forced into an unabashed confrontation with life. We turn back from those things we did that we would have been better off not having done. And we look around us and watch the natural world doing the same thing. Autumn approaches and we see the world drawing into itself. Visible growth slows down. Animals and plants take the time now to collect their energies and focus their activities on what they must do to ensure that they also are inscribed in the Book of Life for the new year.

The Bible also gives certain literary hints that this may have occurred during the procession of generations on the earth. For ten generations after the creation, the Bible tells us, the ways of humanity deteriorated: from the murder of Able by Cain his brother, through the haughty building of the tower of Babel, till the tenth generation, that of Noah. It was then after ten generations when repentance was possible but didn’t occur that God decided to clear away the dross and begin again. God made a new attempt at creation after the waters of the flood receded. (And, on top of that, traditions suggest that the cleansing flood even began in Tishre. However, even the descendants of Noah did not live up to God’s expectations. Not much time passed before they, too, began to act in evil ways. But this time (again, after ten generations—a nice literary device), instead of destroying the world and all humanity, God tried a different method: focus on one part of the world, one family among all of humanity, the family of Abraham. God decided (the ancient rabbis tell us) that through the descendants of this couple (Abraham and Sarah), the world would be inscribed for life. Ten generations after Noah marked the birth and selection of Abraham and Sarah; a new attempt to create a perfect world.

And, I’ve heard, another ten generations passed since the time of Abraham during which period we lived through the most trying time of our early history. After famine occurred in our land we went to Egypt where we were tricked into slavery and began serving other gods. A new creation huddled in the shadows of Pharaoh’s storehouses, ready to take its place in history. From the family of Abraham and Sarah to the Nation of Israel. In our struggle toward formation we received ten constraining Commandments.

blacksmith at work

Like the heated iron of the blacksmith, put into the hot coals, then beaten on the anvil, we were shaped, concentrated, compacted till our formative process was completed and we were cast into the world, ready to re-enter our land. Ten generations of creativity shaped by limitations and formed by contractions: Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham and Sarah, Abraham and Sarah to Moses.

we have the ability to create our selves

Our preparation begins now, at the beginning of Elul, as our creation begins on Rosh haShannah. For ten days we concentrate those energies, cleansing ourselves, purifying ourselves, to be inscribed into the Book of Life on Yom Kippur.

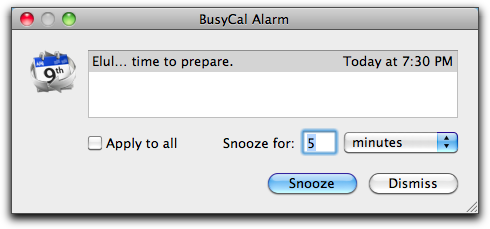

helpful reminders

But, we often need help. We need reminders, alerts and alarms to get us to cut back and encourage us to begin the process. The shofar helps.

That other name: Yom Teru’ah, the day of the Shofar Blast. Yes, even the youngest of us knows that on Rosh haShannah we blow the Shofar. But to name this great and awesome day after a musical instrument or a part of an animal? There must be more to it all. And there is. The clue is, of course, in one of the Torah readings for Rosh haShannah: the Akedah, the binding of Isaac. The story of Abraham and Isaac’s journey proceeds at an unbearably rapid pace, and for a time it truly seems that Isaac will actually be sacrificed. As though, like us, Abraham must cut back on an aspect of himself at this time of year to contemplate his creation, and Isaac (perish the thought) is what must be given up! In fact, when I first starting thinking these thoughts, I awoke from a nightmare in a sweat, having dreamed that indeed Abraham had actually sacrificed his son as a paring away of his own unruly growth. We all know that Isaac was not sacrificed, and yet, the Bible’s story is awesomely powerful and compelling each time we read it.

awesome horns

What was it that Abraham offered in place of Isaac? The ram. We read that an angel told Abraham not to slaughter his son. I like to think that this was actually the braying of the ram stuck by its horns in the thicket that caught Abraham’s attention. It was the ram’s horn itself that signaled the change in the turn of events and determined that even if Abraham was to draw back on his unbridled growth, he was certainly not to sacrifice his son, his only son, whom he loved, Isaac. Similarly, the shofar, this ram’s horn is also a symbol, and when sounded, a cry out to us that it is time to change our ways.

The word [many browsers do not display the pointed Hebrew well] שׁוֹפַר (shofar) is, of course, a noun, but when pronounced: שִׁפֵּר (sheepair), it becomes a verb and actually means to improve and to cleanse! The ancient rabbis, aware of the poetic possibilities inherent in this double meaning taught that God says: If you cleanse your deeds, then I will be to you like the shofar. Just as the shofar draws in the air from the narrow end and emits it from the wide end, so I will get up from the throne of Judgment from which I make tight, stringent, decisions and sit down upon the throne of Mercy, and turn for you the attribute of judgment into the attribute of mercy.

We can also see this in the actual shape of the shofar, its sound and the method for producing that sound. It takes great concentration of mind and muscle at the narrow end of the shofar, before the broad powerful tones come out the open end. The tones themselves play a role in the concentrating and redirecting of our creative lives. The ancient rabbis tell us that, metaphorically, the sound of “Teki’ah” urges us to beg for God’s mercies. Then, the sound of “Teru’ah-Shevarim” actually shatters the enslavement of our hearts to unworthy desires.

A story is told about the Western Wall of the Temple in Jerusalem which has been the object of friction between Arabs and Jews for many years. In 1929, the British controlled the area. To appease the Arabs, the British forbade the traditional sounding of the shofar at the Western Wall at the end of Yom Kippur. But the Jewish underground of the time ignored this prohibition.

That Yom Kippur as the service at the wall came to the final prayers, the Ne’ilah. The cantor chanted the final Avinu Malkaynu. He added a phrase to the prayers– “Avinu Malkeinu, Our Father our King, we have the shofar; draw a circle around us.” The British guards were oblivious, but the Jews understood the Hebrew, but did not know what to expect. Suddenly, at one end of the wall, a clear shofar sound came out of a child’s voice. The British police immediately surrounded the child. At that very moment, a Tekiah Gedolah, the long shofar sound for the end of the service for Yom Kippur, reverberated from the other end of the wall.

All the worshipers spontaneously recited “Next year in Jerusalem rebuilt” and then sang Hatikvah.

The following year, a man named Moshe Segal blew the shofar at the conclusion of Yom Kippur. He was immediately arrested by the British. They held him at the police station without food until midnight, when he was released. Only then did he learn how his release came about: the chief rabbi of Palestine, Abraham Isaac Kook had phoned the British and said, “I have fasted all day but I will not eat until you free the man who blew the shofar.”

The secretary had replied, “But the man violated a government order.”

Rabbi Kook replied, “He fulfilled a mitzvah religious commandment.”

Years later during the Six-Day War, when the Israeli Defense Forces recaptured the Old City of Jerusalem Jews gathered at the Western Wall for the first time since 1948. The shofar was again sounded to proclaim the victory and to reassert the right of Jews to worship in freedom at that sacred site. A few months later, at the end of Yom Kippur that year, the shofar was sounded at the Western Wall—by that same man, Moshe Segal. The shofar, once again, sounded as a symbol of continuity, calling us to pay close attention to our actions in this world.

I do not know where I first learned this story. However, something about it does not make sense. The boy referred to “Moshe Segal” is later known as Moshe Meron. The Wikipedia article about Meron mentions that he was born in 1926, but did not make Aliyah until 1936. Either he was too young to have blown shofar in 1929, or was not there until years after the event reported in the story.

Everything about this season as we approach the days of Rosh haShannah and Yom Kippur is directed at encouraging us to draw in our unbridled energies and concentrate them anew in the appropriate directions. We have the shofar, with its sounds, shapes and method for producing tones, signaling us that the time has come to re-evaluate. There are the ten days, between Rosh haShannah and Yom Kippur, symbolic of the various ten generations during which the work of God’s creation contracted and was redirected anew. And finally, and perhaps most simple, we have the example of that created world all around us as it begins to draw into itself in re-creation.

Elul, begins this period that offers us the chance, one might say presents us with the responsibility of renewing the conception and creation of our selves. It is our choice.

The sages said “God will say to Israel, even to all humanity, — ‘My children, I look upon you as if today, on Rosh haShannah, you have been made anew, as if today I created you—a new being, a new people, a new humanity.’ ” On Rosh haShannah, Yom Harat Olam, the day of the creation of the world, we are created with a conservation of our energies so they can be directed correctly. Rabbi Tahlifa said: “The Commandments concerning all sacrifices read: ‘And you shall offer,’ but the one concerning sacrifice on Rosh haShannah reads ‘And you shall make.’ ” However, he continues: “We should read: ‘And you shall be made,’ for after you are dismissed from the Tribunal of Justice above, where you have sacrificed your inappropriate behaviors, and then leave, being blessed by the attribute of mercy, you are as freshly created.”

As a final reminder—which we learn during the shofar service, we should be aware that all good things come to Israel through the shofar. We received the Torah with the sound of the shofar all around Mount Sinai. We conquered in the Battle of Jericho through the blast of the shofar. We are summoned everyday this month and through Rosh haShannah until Yom Kippur to repent through the sound of the shofar. And we will be made aware of the Redeemer’s arrival through the great shofar blast that is yet to occur.

just jew it

| Date: | 2000s |

| Size: | 5.6 |

| Pin Form: | safety |

| Print Method: | celluloid |

| Text | JUST JEW IT |

your lapel buttons

Many people have lapel buttons. They may be attached to a favorite hat or jacket you no longer wear, or poked into a cork-board on your wall. If you have any laying around that you do not feel emotionally attached to, please let me know. I preserve these for the Jewish people. At some point they will all go to an appropriate museum. You can see all the buttons shared to date.

This morning I was reading two articles and struck by their juxtaposition: the latest from Women of the Wall and the struggle to pray and blow the Shofar at the Wall and your reflection on struggling to pray and blow the Shofar at the Wall.

May we soon and in our day see these women for the heroes they are and retell their story too.

Darah,

Thank you for pointing out the juxtaposition. Even if (as I suggest) the story of the earlier shofar blowing at the Wall is not 100% accurate, we should be able to hear women blowing shofar at the wall.

That was one of my reasons for finding a photograph of a woman blacksmith to include in the post.

Why is it pronounced/transferred across languages as “Elul” and not, e.g. “Alol” or even “Alvel”. It’s slow learning without a proper teacher.… and now, ye olde PowerBook doesn’t do well with a lot of the newer web sites that do offer sound files.

Good and sweet new year to you, RMark, and your family.

John,

It’s good to hear from you. I asked a couple of friends for a more authoritative response to your question. The following thoughts come from Dr. Joel Hoffman.

I hope this helps.