Published April 19, 2021, the 78th anniversary (according to the Gregorian calendar)

of the start of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

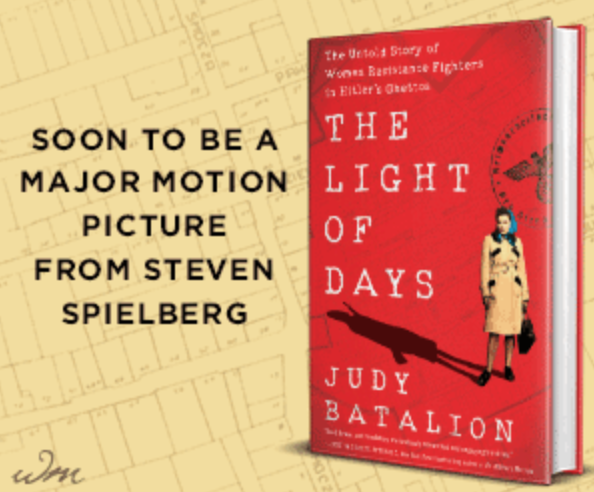

With the publication of “The Light of Days” by Judy Batalion (April 6, two days before Yom haShoa v’hGevurah 5781⁄2021), our attention is drawn to the many young women who fought the Nazis in occupied Poland. I’m very glad to see such focus renewed.

The book has received welcome praise in:

- Haaretz: The Young Jewish Women Who Fought the Nazis – and Why You’ve Never Heard of Them

- The New York Times: The ‘Ghetto Girls’ Who Fought the Nazis With Weapons and Wiles

- The Wall Street Journal: ‘The Light of Days’ Review: To Resist and Connect

- The Times of Israel: Smuggler, fighter, courier, spy: How Jewish women defied the Nazis in Poland

- WBUR (Boston): ‘The Light Of Days’ Tells The Stories Of Young Jewish Women Resistance Fighters In WWII Poland

Not only that, but:

And, at the same time, I’m curious about the book’s subtitle: “The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos”. It is almost as though each generation needs to discover these heroes anew (and at the same time, I’m sure there will long be more such heroes to recognize).

Hannah Szenes

While Hannah Szenes did not fight in Poland, nearly every Jewish child who has had even the most basic Jewish education has been taught of her. Most of these know her poems. They sing “A Walk to Caesarea” (though they don’t know it by its official title). They may even identify with the text of her final poem “Ashrei Hagafrur” which has begun to appear in an increasing number of Haggadot. Her words have even entered the regular liturgy of many congregations as the introduction to the Kaddish. In this text, it is almost as though she writes to us about herself and the other women of whom Judy Batalion writes:

There are stars whose radiance is visible on Earth though they have long been extinct. There are people whose brilliance continues to light the world even though they are no longer among the living. These lights are particularly bright when the night is dark. They light the way for humankind.

In a moment shots will be fired

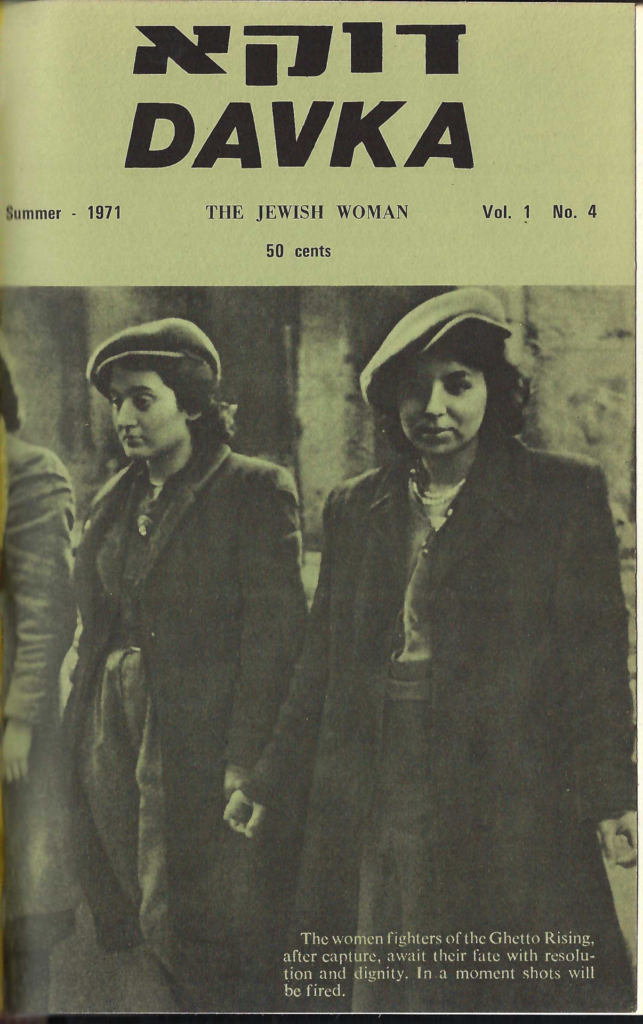

The Summer 1971 issue of Davka on “The Jewish Woman” (Vol, 1, No. 4, when it was a journal produced by Jewish students centered around UCLA) featured a photograph of Rachela Wyszogrodzka, Bluma Wyszogrodzka, and Malka Zdrojewicz, three fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on its cover. We editors did not know their names, but we did what we could to bring their existence forward for a new generation.

The entire cover was also released as a poster and distributed free in the Los Angeles area at the time. Over the years, I’ve seen the poster in a number of homes.

much less well known

…though important especially in this context especially (the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising) is Zivia Lubetkin who (according to her Wikipedia article) was one of the leaders of the Jewish underground in Nazi-occupied Warsaw and the only woman on the High Command of the resistance group Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB). She survived the Holocaust in German-occupied Poland and immigrated to Mandate Palestine in 1946, at the age of 32.

Quiet, the Night is Full of Stars

As children, my siblings and I knew of these women… even if, at the time, we knew none of their faces or names. Friday evenings as part of our family’s Shabbat observance we would sing a wide variety of Jewish, mostly Yiddish, songs. At bedtime, our father sang Yiddish lullabies to us, personalized for each one of us. Dad had recalled the words of his Shule teacher, Mr. Finklestein, in Cleveland, OH where he grew up, who had said:

Any language that people didn’t sing to their children in lullabies would not live.

And so, we learned the words to these songs, even while we, by and large, did not know what they meant. Among the songs we sang before bedtime was one that was definitely not a lullaby, though its melody is soft and soothing. It is more of a love song. When Mom made a recording of the many songs sung to us as children for Avigail in 1987, she included this one by Hirsch Glick (though it was usually sung by Libbe):

שטיל די נאַכט

שטיל די נאַכט איז אויסגעשטערנט

און דער פֿראָסט האָט שטאַרק געברענט

צי געדענקסטו ווי איך האָב דיך געלערנט

האַלטן אַ שפּײַער אין די הענט

אַ מויד אַ פּעלצל און אַ בערעט

און האַלט אין האַנט פֿעסט אַ נאַגאַן

אַ מויד מיט אַ סאַמעטענעם פּנים

היט אָפּ דעם שׂונאס קאַראַוואַן

געצילט געשאָסן און געטראָפֿן

האָט איר קליינינקער פּיסטויל

אַן אויטאָ אַ פֿולינקן מיט וואָפֿן

פֿאַרהאַלטן האָט זי מיט איין קויל

פֿאַרטאָג פֿון וואַלד אַרויסגעקראָכן

מיט שנייגירלאַנדן אויף די האָר

געמוטיקט פֿון קליינינקן נצחון

פֿאַר אונדזער נײַעם פֿרײַען דור

Quietly the night is filled with stars

and the frost burned

Do you remember how I taught you

how to hold a revolver in your hands?

A girl, a little fur coat and a beret

and she holds tight a Nagan pistol in her hand

A girl with a face of velvet

watches for the enemy’s caravan.

Aimed, shot and met the target

her little pistol did,

A car, nice and full with weapons,

she stopped it with one bullet.

Before daylight, she crawled out of the woods

with snow-garlands in her hair,

cheered on by the small, dear victory

for our new, free generation.

Many artists have covered the song some even in English translation. However, to keep this more personal, here is my mother introducing and singing it to her grandchildren from her 1987 tape:

Sho’a Nightmares

Originally published June 2, 1999.

In April of 1997 I wrote (as an aside) to a forum of colleagues:

I think every teenage Jewish child ought to have a week of Sho’a related nightmares. If we can reenact the Exodus and living in Sukkot, why not the Sho’a?

Only one person responded. However, that response was quite intense. I will not quote from that response but paraphrase some of the exchange that ensued

My correspondent strongly disagreed with my suggestion that we “impose” Sho’a nightmares on children. Suggesting that is one thing for an individual to make a conscious decision to engage in the particular painful exercise, and quite another to impose it on someone. My correspondent suggested that (while certain that I had not intended to convey such an idea) none of us are put on earth to create new nightmares or forms of abuse.

And so, I responded. Here is my thinking:

I decided over 25 years ago [that would have been around 1972] that each Jewish child should have a week’s worth of nightmares. Of course, there is little that I can do to “enforce” this, but I can make experiences available that can enable them. I recall being at a Zionist youth movement camp in the mid-’60s and shown the movie “Night and Fog.” The film had graphic footage of the death camps. At home, I had books my parents had brought into the house with still photos of the horrors. I had spent hours exploring these images.

I was older (approximately 20 years old) when I tried to get into the life of the boy with his hands up being led from the Ghetto. I spent months with him, I kept his image before me daily, his image turning a fiery red as the black closed in on him. [There are some who suggest that he may not have died in the Sho’a!]

Of course this was all self imposed and voluntary. Did it scar me? I think not. Perhaps colleagues who know me could respond better.

I have not changed my mind. I still find nothing abusive in this.

A week during a lifetime is a brief span.

- To imagine what it means or feels like to be a Jewish infant tossed into the ovens alive because the Nazis wanted to save the 0.5 cents the prior gassing would have cost….

- To imagine for a week what life was like for a teenager living through the Sho’a….

This is not a terrible burden on a child. I know children who have nightmares from seeing a popular Hollywood movie, they all live through them. Do we prevent our teenagers from seeing such films because they might have nightmares afterward?

If my children can identify with these children of the Sho’a, learn from them and recognize the holy spark that exists in each person, regardless of age, gender, social standing, location in the world, I don’t think I’ve terrorized them horribly.

Again, the point I made was in context of experiencing :

| בְּכָל־דּוֹר וָדוֹר חַיָּב אָדָם לִרְאוֹת אֶת־עַצְמוֹ כְּאִלּוּ הוּא יָצָא מִמִּצְרַיִם B’Chol Dor vaDor Chayav Adam Lirot et Atzmo K’Eelu Hu Yatzah miMitzrayim |

and I add:

| בְּכָל־דּוֹר וָדוֹר חַיָּב אָדָם לִרְאוֹת אֶת־עַצְמוֹ כְּאִלּוּ הוּא יָצָא מאושוויץ B’Chol Dor vaDor Chayav Adam Lirot et Atzmo K’Eelu Hu Yatzah miAuschwitz |

In order to K’Eelu Yotze miMitzrayim we need to experience some of what Mitzrayim was.

On continually retelling the Sho’a, I remember an anecdote from Isaac Deutscher’s book “The Non-Jewish Jew” in which he wrote of a Melamed with bright red hair who sat before them in cheder. Every day all he did was tell of the crossing of the Red Sea. Each day the story was new as different details emerged from his telling. Each day the Kinder experienced the wonder of redemption.

Our correspondence continued with an examination of my quoted text.

Our rabbis tell us that in order to qualify as a Chacham we must take on the responsibility of seeing ourselves as if we had been liberated from Egypt and that if we deliberately exclude ourselves this makes one a rashah! My desire to have our teens experience the Sho’a in a similar way suggests that if they do not, the are r’shaim.

In addition we are not obligated to experience the specific horrors of slavery in Egypt but recognize that we are free from ultimate oppression.

Yet, in the Seder itself we do a number of things to remind us of what slavery must have been like. We dip karpas in salt water to remind us of the tears our ancestors shed. We eat the maror to remind us of the bitterness of slavery.

I had not written about what I felt I had gained from my “exercise” and my correspondent found that unfortunate, suggesting that when we speak of our own personal experience, we enable others to find a common thread and build on our ideas, or not. On the other hand, when we tell people what they should do, we encourage submission to our “suggestion” or that they defy us.

We speak of Yitziat Mitzrayim as a metaphor for the process of rebirth. Yet (according to my correspondent) we are not sufficiently far from the Sho’a to appreciate its metaphoric value. My correspondent suggests that we haven’t been able to metaphorize the Inquisition! (I’m not sure of that, I have read a variety of accounts that suggest that the Kabbalah of Tzfat is a metaphoric response to Grush Sfarad.)

It seems that I had gotten dangerously close to some very delicate issues. My suggestion that children have nightmares raised questions of why we have such concepts as harassment and abuse. Suggesting that some of us are more powerful than others and that when the more powerful tell the less powerful that they should do something, they are imposing it.

OK, let’s take a step back and a deep breath.

I didn’t have the opportunity to discuss the Sho’a with the family. Too busy working out math problems, helping with practicing La Bamba, catching the last 20 or so minutes of the current sit-com, you know, the normal things of life. The things that the Sho’a prevented.

Can I impose? Yes: I impose a bedtime, I impose a dress code, I impose taking vitamins….

But I wrote initially: “should” not “must”. Do I feel there is some kind of Mitzvah to experience the Sho’a? Yes, but that is a metaphor. And here is where I did not make myself clear.

I was asked:

- When we say they should experience something, what do we mean?

- Why should they experience these nightmares?

- To be whole people? To be compassionate?

- To be worthy of our attention?

- To be good Jews?

- To be an adult?

- To be decent?

- To be clones of us?

To which I respond:

| Why do we say that every Jew should consider themselves as having been freed from slavery in Egypt? So much of our texts harken back to the experience in Egypt as a source of lessons. |

I don’t need clones. I often see aspects of myself in my children about which I feel uncomfortable… other aspects I enjoy. I know and love the fact that they will develop into independent adults taking the tools that my wife and I have made available to them and rework their lives and their world. My task as parent/adult (even rabbi in the greater sense as in with more than my children) is to make those tools available to the next generation (i.e. raise up many disciples).

I have never described how I benefited from my exercise of identifying with the boy in the photograph.

How have I benefited? First, nothing appears here on this WWW site other than attempts to celebrate the lives of the communities destroyed by the Sho’a and liturgies that heighten our awareness of the Sho’a in the hope that we might incorporate this aspect of our people’s experience into our lives as we did the experience of Slavery in Egypt.

Beyond this I’m afraid I cannot point to anything tangible.

Perhaps someone with keener insight into me as a person would know. It is hard for me to know. The only me I am is the one who has lived this way. What would I have been like had I not done these “exercises”?

how early?

Indeed, how early should Jewish children be introduced to the Sho’a? An article at the JTA (April 8, 2021) suggests very early is not a problem: “Growing up in Anne Frank’s shadow, my kids have known about the Holocaust since before they could speak”.

When our children were young (at the time the original version of this post was written) I would prepare a “special” dinner for Yom haSho’a v’hGevurah. I set the table with the usual white table cloth, as for Shabbat, and put out the candlesticks, but without candles along with a yahrzeit candle. The dinner itself required more advanced planning. I made sure we had bread in the house that had gone stale (at least stale) and the “main course” consisted of not much more than weak potato soup along with some wilted vegetables. I see on the Web that there are now communities that hold seders for Yom haSho’a v’hGevurah. There is even a fairly elaborate Haggadah (PDF download) for the event.

full circle

Also on April 6, an article about Batalion’s book appeared in Tablet. Interestingly enough its focus was not on the adult text to be published that day, but on a companion text for “a young audience”. It’s interesting to note that her young readers’ book is designed for pre‑, and early teens.

How is it possible to adapt such a serious adult book for a young audience, ages 10–14, without losing its power? For Batalion, who grew up in a family of Holocaust survivors, this involved remembering what was important to her when she was that age. But it was also about how important she had come to believe it is for young Jews to learn about female resistance narratives that, historically, had been occluded or ignored.

In editing the text, the non-Jewish editor commented:

“You don’t want to traumatize kids to the point that it closes them down and makes the story inaccessible because they can’t process it,” said Conkling. “So, you are trying to let them know what happened in essence, without spelling it out in detail.” For example, in the adult version one particularly graphic scene is described in which a German soldier grabs a baby from its mother’s arms and kills it in the most horrific manner while the mother and other children watched the atrocities, wailing uncontrollably. In the young reader edition, the scene is deleted, and the text instead explains more generally that people of all ages were taken away by the Germans and sent to Auschwitz to die.

I imagine that older teens can handle more graphic material.

| Date: | 1981 |

| Size: | 5.6 |

| Pin Form: | clasp |

| Print Method: | celluloid |

| Text | NATIONAL COMMEMORATION זכור געדענק Remember 6,000,000 WARSAW GHETTO UPRISING |

your lapel buttons

Many people have lapel buttons. They may be attached to a favorite hat or jacket you no longer wear or poked into a cork-board on your wall. If you have any lying around that you do not feel emotionally attached to, please let me know. I preserve these for the Jewish people. At some point, they will all go to an appropriate museum. You can see all the buttons shared to date.

The image at the top is part of what remains of the wall of the Warsaw Ghetto.

The photo was taken on April 16 (Easter Sunday), 2006.